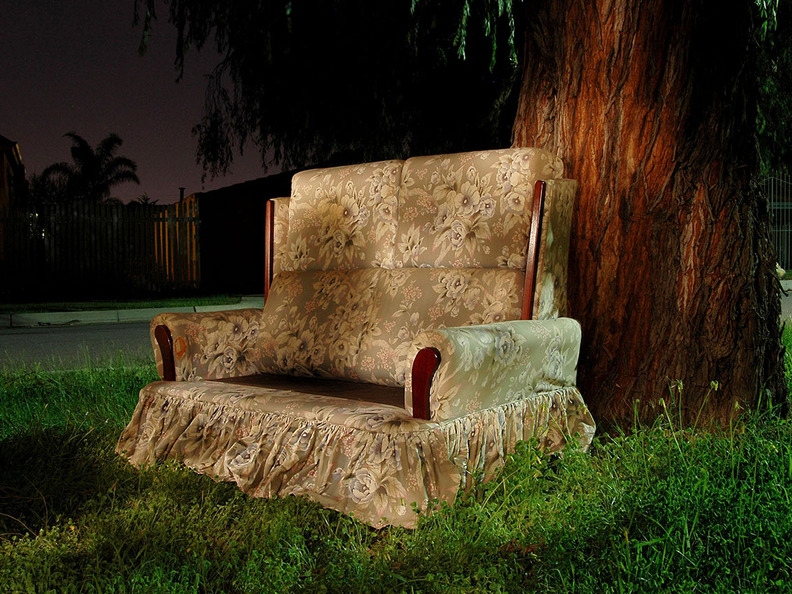

RAGAMUFFINS - 2009 - 60cm x 80cm - Digital print, archival Pearl paper

RAGAMUFFINS - The opening at PCP by Robert Cook, Associate curator of Contemporary Art, Art Gallery of Western Australia - Extract

"... First, because they surround us, Christophe’s Ragamuffins. As catalogue-essayist Claire Krouzecky notes, these couches, lounges and Lazee Boys and Girls are not (as I had initially assumed) constructed images, but instead are actually found in the wild…and then, as Flavia pointed out to me, rather artfully lit, so that they look staged. In working in this way, these shots that are the result of Christophe entering David Attenborough-mode, locating them in their unique habitats, are also a way of foregrounding that act. Accordingly, the work conveys an implicit adventure in the act of scouting, locating, and then presentation. It is not a stumbling across, and the management of an aesthetic from that, but the production of a theatre of urban decay.

Of course, this process sits both neatly and oddly in relation to its motif. After all, the lounges are strangely organic and monstrous, truly abject. Indeed, they don’t just sit outside the flats, houses, fences and houses-to-be, but glom there. They ooze like a sweating summer house guest cheaply dressed in tight synthetic polymer blend who you just can’t get rid of. They’re like furniture as Homer Simpson, degraded and degrading. And maybe, too, they’re like cockroaches, the kinds of beings which, when everything else goes up in nuclear dust, will remain, squishy and shabby sure, but the only true reminder of the species that we once were. Different species scientists will examine them, making casts of the indents in order to form what they think are realistic replicas of the people we once were.

They have this seeming strength because the oily imprint of sloth has given them more super than human powers and this is because they sucked our life and our lives into them. I mean, who really knows how many bodies have been sucked into their spring and foam depths? It is for this reason that we possibly find them confronting. They are waiting for us – as cushioned Venus fly traps, sprung bogs, stitched quicksand fugs.

And, weirdly, against this, the houses, the flats and the like, feel positively life-affirming. These structures of dwelling have a set of rituals around which people flow and that the sofa sits opposed to as a septic and sarcastic critic. So, now, in Christophe’s works, and isolated from the other interior furniture we can see the couch for what it really is, a sign of relaxation gone bad, gone sad, gone toxic. A sign of a grunge past that has not gone away, that follows us and lies in wait to bring us down. We can see that, though technically supportive, there is nothing uplifting about them at all.

Yet all of this is entirely conjecture. Maybe I’ve got it wrong. The couch could be a sad, misunderstood outcast, for whom, in a world of action, it cannot keep up. It has no place in our go-gettum, power-grabbing lives. So in this way, Christophe’s lovingly monikered ragamuffins speak to fears of complacent living, about our desire to transcend this by distancing ourselves from those who fail to act toward becoming couch-less men and women of substance, while simultaneously (and perversely) positing that ‘no-action’ will win out in the end. Weirdly, therefore, Christophe’s show gets at a cluster of feelings and associations about how we live and how and who we scapegoat, and the fear and the pleasure of all of that..."

Robert Cook

Like shadowy urban vagrants Christophe Canato’s armchairs and sofas sit, orphaned by their human counterparts, in the night-time street light. Left with the cogent marks of habitation, these armchair-orphans remain to carry the stigma of their lived existence, silently bearing the burden of the consumerist, disposable lifestyle they serve and providing a telling vestige of our most intimate and peculiar of behaviours.

As in his previous bodies of work, Canato once again positions us as voyeur; witness to a strangely intimate snapshot that simultaneously fascinates and disturbs. Shooting his subjects in formal portrait-style compositions, there is no ambiguity as to what is intended for us to see. Canato provides a window into the domestic setting, a morbidly intriguing view of the living habits of others. Despite the complete removal of any physical life in the photographs, they are undoubtedly alive: they reek of human habitation. They are portraits of the stain of daily living, documents of a consumerist society. In the cover of night they quietly live on as the melancholic remains of ghosted individuals.

Beautifully shot using long-exposures, there is a strong poeticism to Canato’s work, despite the gritty subjects. It is this duality in the image that fascinates the artist and provides a unique view of what is otherwise familiar, banal even. This fascination reveals itself in his continual return to subjects of juxtaposition. In the case of Ragamuffins, soft upholstered furniture against the harsh urban environment, the private domain of the home brought brazenly into the public realm, and above all, Canato’s remarkable ability to achieve soft colours and warmth in harsh artificial street lighting.

What appears to be a contrived and constructed photograph is in fact a testament to Canato’s skill as a documentary photographer, whose eye for natural composition in everyday arrangements means the photographs actually have little construction involved on the artist’s part. Rather, Canato shoots what he finds, untouched as much as possible. These ordered and seemingly thought-out arrangements of furniture on verges are in fact the work of the people who placed it there, not of the photographer who found them. Such fascinating documents, the pictures are then, of the need to arrange compose and organise, ever inherent in human nature.

Again, what we are left with are the traces of activity, the marks made by previous owners, distilled in the arrangement of cushions and chaise pillows on and around the armchair skeletons. Once more, the ghosts of past inhabitants are unwaveringly present; their imprints remaining not just physically in the seat dips and dirt marks, but also in the composition of the sofas on the verge.

Canato’s Ragamuffins are an enquiry into the social schema of our time, and the sizeable mark left by humans on our lived environment, socially, culturally and materially. Not only this, but the comparisons to homelessness and nomadism abound, driving home Canato’s continual and ever growing interest in the patterns which repeat themselves in our social structures, through to the consumerist lifestyle, and finally, to the essence of human habitation, the habits of humans.

Claire Krouzecky