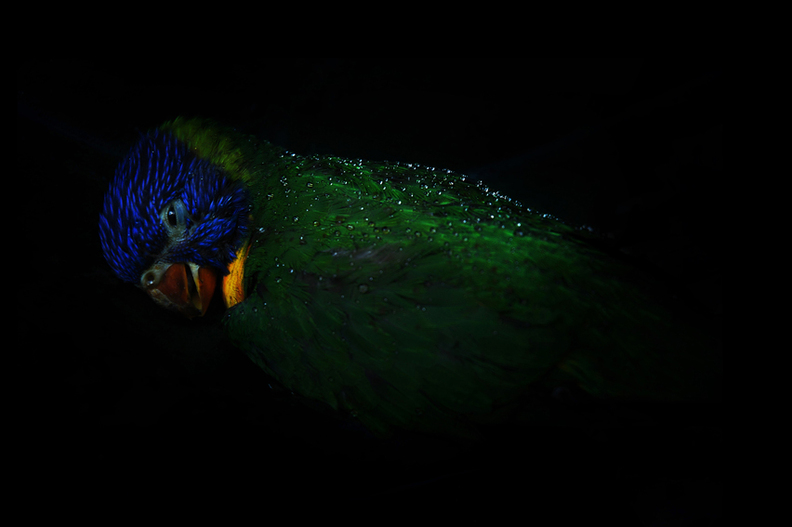

RICOCHET - 2014 - Digital photographs, 90cm 60cm, edition 5

Alasdair Foster

Alasdair Foster is a Curator and writer specializing in the Pacific region. He was the founding director of Fotofeis, Europe’s largest photo festival in the 1990s, Director of the Australian Centre for Photography (1998-2011) and Managing Editor of Photofile magazine (1998-2008).

The Age of Becoming.

It is an age of becoming. A voyage already begun; the maternal haven to stern and the churn of adolescence still to come. It is a time when the brain is plastic; knowledge is sketchy but tacked together with the rich embroidery of the imagination. These are the dog days before puberty.

Christophe Canato’s photographs are not portraits but portrayals. It is not biography that they unfold so much as a state of being. These are evocations of a time it is difficult to reconstruct as an adult. A time when one knew less and believed more; a time when one trembled at details but embraced the ineffable. Fleeting insights of intuition.

Set in an elegant blackness and lit for the warm chiaroscuro of a Renaissance painting, each image presents a conundrum. A game. A play of ideas. A boy appears with thorns along the ridge of his nose. A biomorphic hybrid hinting at dragons, dinosaurs or perhaps a rhino, but also a metaphor for a curiously prickly exterior adopted as camouflage for uncertainty.

Another boy with impossibly large eyes regards us from under his animal pelt hood. He appears frail yet empowered, perhaps by some shamanistic magic of his own conception. Another is lost to the sounds of the sea whispering to him from deep inside a conch. The enchantment of this phenomenon, lost to the adult world, has transported him far from the here and now. To what distant shore has his mind journeyed?

Entitled Ricochet, Christophe Canato’s body of work embraces the uncertain trajectories of the childhood experience. Just as the stray bullet glances tangentially from the rock, so a boy’s perception refracts from the surfaces of his mind like sunlight on a crystal, scattering in iridescent scintillation. But, to the Francophone artist, ‘ricochet’ has another meaning, for in France it is the name given to the pastime of skimming flat stones so that they hop across a still expanse of water. A game in which, for a few moments, energy defies the baser logic that stone must always drown.

Christophe Canato’s images of boys are accompanied by photographic still-lifes. A tooth and two buttons, one of horn the other mother-of-pearl, are both curios and talismans. They speak softly of what lies beneath the surface and of the imminence of death. Wrapped in a handkerchief they are carried with their new owner, treasures to show to others and auguries to contemplate alone.

A dead mouse, the amber remains of a lizard, the mysterious hump of (perhaps) a termite nest; an archetypical pap-shaped bivouac of woven branches, the natural helicopter of a sycamore seed and a dandelion clock. The mind of a boy is a cabinet of curiosities.

This is a tightly constructed body of photographs through which a number of complex ideas reverberate. It is not just that the boyhood imagination is inventive, it is also collective. Ideas are shared, actions mimicked, styles adopted and tales believed. The period before puberty is one in which we first discern the expectations the world has of us. Having left the close embrace of the maternal to explore the nature of being an individual, the child discovers demands are being made, ambitions set. The mould begins to wrap around the clay. There is tension between a desire to conform and the urge to discover what might be possible.

A boy sits with his eyes covered by a friend; in such a state he must rely upon his companion to know what might be seen. Is this a prison or a place of safety? Is it better to do as others do, see the world through their eyes, or experience it directly and perhaps find oneself lone? It is only in adult-life that we come to understandings that all innovation is spun from what already is; that every individual, however eccentric, is an expression of the same vocabulary of being.

But do we, as adults, also have something to learn from these long-lost childhood days? In growing older and wiser, did we, along the way, let go of something precious? The willingness to believe. The charm of imagination to imbue the detritus of the ordinary with its own peculiar magic. To see the world anew and to marvel.

Paola Anselmi

Freelance curator and arts writer Paola Anselmi is based in Australia. She is currently undertaking a PhD in Photography at the University of Western Australia.

The Stillness of Suspense

Christophe Canato’s photographic work sits within a tradition of artists whose practice is steeped in contemporary romanticism and social symbolism. While Canato’s work is certainly haunting and mesmerizing, it is not sublime, but rather links to a kind of ‘ironic romanticism’, which reveals the inconsistencies and the contradictions of contemporary life.

While Canato’s photographs are not explicitly autobiographical, they are informed by a personal investigation into his own male identity, the sense of dislocation, relocation and transformation in a changing western society.

Throughout his 20-year practice, from earlier series such as Pièces à Conviction(2001), Ragamuffins (2009), Women of Jerusalem (2011) andRicochet (2013),one quality that underscores his photographic oeuvre is a quiet, pervasive sense of drama, a performance that is soundless and yet piercing. Over time, this sensibility has matured and has become increasingly sharp without ever being confrontational or provocative.

The sense of communication and accessibility is paramount in all of Canato’s photo-media works. Whether through a household object, a child, an insect or a bird, his subject matter is never aloof and indifferent. The viewer is always invited, and at times sweetly persuaded, to enter into a dialogue free from condescension and open to personal and subjective engagement.

Canato’s subjects, often represented with a stoic sense of determination and self-awareness in a moment of partial surrender, are often disarming, sometimes vulnerable and aware of the viewer’s presence. These subjects are often bound by a deep and concentrated blackness, yet nothing is static and the subjects are arrested in a transient pause, the momentary stillness between actions, where movement is only implied. One of the strengths of Canato’s photographs is the suspense of expectation.

From the very beginning of his artistic practice, Canato has increasingly focused on extremes and the duality of opposites in his work, proposing multiple directions in his photographs: the child and the adult, past and present, light and dark, attraction and repulsion. The image itself sits in the uncomfortable middle area, where the tension that keeps the balance between opposites lies.

There is no ‘grey area’ in Canato’s photographic work, as this would imply a sense of uncertainty. As in a film noir script, every action is investigated, every object is bagged and every scene is scrutinized. Every element is important to lead the viewer to question not only the image and its meaning, but their own responses to it and their own realities. Each photograph is meticulously composed, all superfluous elements are removed, and the minimal yet rich remainders all have a function, they act as keys to new interpretations and narrative journeys.

Often, important works that question our global and shared status quo develop with a slow burn. Over the last two decades, Christophe Canato’s photo-media practice has been measured and constant and importantly, thematically and conceptually coherent. Christophe Canato has developed an impressive volume of outstanding photographs and video based work that fits convincingly within a contemporary critical current underpinned by interests that question the contradictions and ambiguities of social paradigms.